In which I have no patience to wait 'til by and by*

A personal take

Fun fact: Many Bitcoiners believe that Bitcoin’s 10-minute block time is not too slow and that having a fast block rate is not useful.

This is a very disturbing stance, since I’ve invested lots of conceptual and practical efforts into accelerating block times based on the premise that fast confirmation times—or “Liveness” in consensus terminology—matters, and it will break my spirit if this proves in vain. It is with the noble objective of making sure I’m needed that I present to you below the case for fast Liveness. I believe it matters.

The case against fast confirmation times

The elephant in the room: No one needs Bitcoin to be user-friendly; it is here to be HODLed, not used. Bitcoiners rarely pay with their bitcoins, a true Bitcoiner never sells them, and we can all just hope to be as sacred as He who never even touched his bitcoins.1

While obnoxious, this position is not ridiculous. The most difficult part solved by Bitcoin was the creation of a stateless algorithmically-controlled money system. Of course, this money should be transferable and, ideally, conveniently so; but the main achievement is not “good UX money.” And if improving Bitcoin’s UX would compromise its resilience, decentralization, or social scalability, it’s not worth it.

This position does imply, though, that a different cryptocurrency will prevail as a cryptocurrency that’s intended to be used by the masses.

The case against fast block times

If you ever wondered why you are not invited to VIP Bitcoin parties, it’s probably because you let it slip that you think fast blocks are cool, which proves your deep lack of understanding of our cult’s core principles. This is where continuing reading this post can become very helpful for you.

In order to understand what system parameters improve confirmation times, and when, we need to describe the flow of a crypto payment authorization.

If you are a merchant receiving payments in crypto, you must wait until transactions are sufficiently irreversible before confirming them to the payers. There are two paradigms on how this waiting is done. In the first paradigm, you wait for a sufficient amount of blocks to pile atop the transaction in the ledger; here, accelerating block liveness will shorten your waiting, namly, the confirmation time. In the second paradigm, you wait for a sufficient amount of (absolute) time to pass before confirming; accelerating block times will not shorten your waiting.

Essentially, in the first paradigm you wait until enough blocks are mined so that the [hypothetical or invisible] attacker’s chain is shorter than the ledger’s main branch, with sufficiently high degree of certainty; in the second paradigm you wait until enough time passes so that the attacker’s budget has drained. The two paradigms correspond to two threat models.

Illiquid vs. liquid mining

Bitcoin miners spend only a few 105 USD/hour on protecting our transactions. Their revenue from mining—a.k.a. the security budget—is on the order of a few 106 USD/hour. Contrast this with Bitcoin’s market cap of a few 1011 USD, and you’ve got yourself wondering how 106 can protect a 1011 asset—surely there are ways to make much more than a few millions by attacking the Bitcoin giant, by reversing the ledger after an hour or two. For instance, if you are a financial whale that has the ability to short Bitcoin,2 or if your name is Vitalik and you want to double spend bitcoins to keep Bitcoiners from being obsessed with something other than Ethereum’s success. Definitely worth a few billions.

Well, since the Bitcoin mining market is highly illiquid, an attacker cannot get hold of temporary hashrate even if he has a few spare 106 USD. Instead, the attacker will need to invest in manufacturing or purchasing mining ASICs, which are priced for long term mining, and are indeed on the order of magnitude of 1011 USD. It is the capital expenditure of Bitcoin miners (CapEx), therefore, that protects our Bitcoin transactions, not their operational expenditure (OpEx). The high CapEx is what lends credence to our assumption that the majority of hashrate is held by honest miners (on which I’ll elaborate below), whereas the OpEx seems too low relative to the potential gain from an attack.

But many cryptocurrencies operate in liquid mining3 environments wherein significant hashpower is available for temporary rent on NiceHash; NiceHash is a marketplace for renting hashpower, typically relating to GPU-dominated coins. Now, if attackers can temporarily rent large amounts of hashrate, there’s no reason to assume that they do not control a majority of it, during the attack window. Indeed, most of the 51% attacks on small cryptocurrencies have occurred in GPU-dominated mining environments. In these environments, one needs to think about the security of the system in different terms: Instead of the honest majority assumption, the security assumption underlying liquid mining environments is that a 51%-attacker’s budget is limited and therefore he is unable to spend OpEx—by mining with GPUs or with rented hashpower—for long attack windows.

The following table compares illiquid and liquid mining environments.

| Dominant mining machine | Dominant mining expenditure | Type of attacker protected against | Security assumption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illiquid | ASIC | CapEx4 | In-band | attacker_rhashrate < 50% |

| Liquid | GPU | OpEx | Out-of-band | attacker_budget < $M |

Payment authorization flows

In the liquid setup, since the attacker’s budget is affected by the duration of the attack, payments can be confirmed safely after enough time has passed. In the illiquid setup, since the block race between the honest majority and the attacking minority is governed by block creation events, payments can be confirmed safely after enough block creation events occurred. We conclude that block liveness matters in illiquid ASIC-dominated environments. QED.

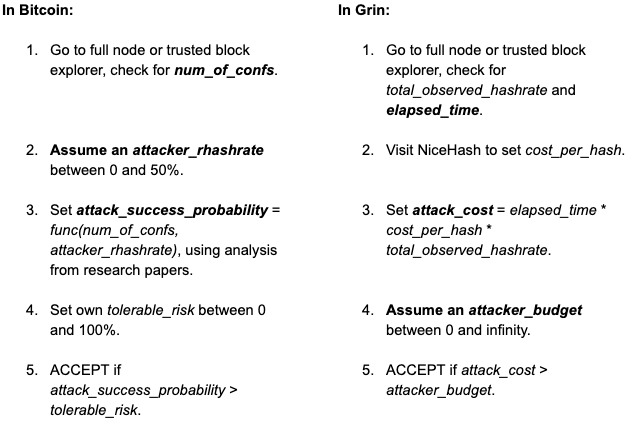

Here is a payment authorization flow comparison between Bitcoin and Grin:

The above compares the payment authorization flows in illiquid, or Bitcoin-like, vs. liquid, or Grin-like, mining environments.5 Observe that the attack cost—hence the waiting time for confirmation—does not depend on the block rate, in the liquid setup. In contrast, in an illiquid environment, func(num_of_confs, attacker_rhashrate) does depend on block creation events; so accelerating block times does in fact shorten confirmation times.

On the altruistic majority assumption

It is useful to recall Satoshi’s original security analysis wherein neither honest miners nor the attacker regard their own incentives: The honest 51% follow the honest mining strategy altruistically, and the malicious 49% are irrational (a.k.a. byzantine) and attempt to maximize the damage inflicted or the success probability of the attack (and not the profit!6). This is not to say incentives are not underlying the core logic of the system, rather that questions about why a miner would mine honestly or maliciously are discussed outside the security model; they are macro level questions, whereas a client accepting transactions should concern herself with micro level dynamics. It is these macro level arguments that may justify our honest majority assumption. Beware! My thought process here makes “the dumbest assumption of all,” according to Nick Szabo—namely, that Bitcoin’s security strengthens as more CapEx is invested into it. I admit I don’t get it.

I’m emphasizing Satoshi’s altruistic majority assumption because some people argue that OpEx is essential to security and that without it an attacker could use the same mining resource to mine both good and bad blocks simultaneously (similar to the nothing-at-stake criticism of PoS). My counterargument is that the costless simulation phenomenon is noncontinuous and holds only in the absolute zero OpEx case. But either way, this micro level reasoning with respect to mining requires a different—and, in fact, weaker—security model, namely, one which treats malicious (and honest?) miners as rational profit-maximizing agents participating in a game. Understanding these mining dynamics requires thorough analysis of optimal mining strategies, and an attempt at that was started here; also see this paper. These results show that a rational attacker can in fact maintain long-term profitable attacks, which questions the assumption that attacks are costly and which intrigues rephrasing or rethinking the security model.

In other words, I disagree with Bob.

ASICs are energy-efficient PoW

I’m not a fan of liquid mining systems. Yes, they are more democratic; anyone can plug in their GPUs, opt in, plug out, opt out. No barrier-to-entry, no barrier-to-exit. But this is a double-edged sword; “OpEx-heavy” means you burn the security budget by using it. It means the security—by implication, the ability to accelerate confirmation times—can only scale linearly with the amount of resources burnt on the system. To be very very very secure, we need lots and lots and lots of computational resources burnt for us. It works, but it’s inefficient.

In contrast, “CapEx-heavy” means you are protected by the miners’ investment, which locks them into the system and which is not burnt with every new mined block (outside of a negligible hardware wear).

It’s like the difference between buying a house and renting it. Your monthly mortgage payment might be similar to the rent, but you never enjoy a month’s rental payment beyond living in the residence for that specific month.

An ironic implication: Green PoW attempts which use available commodity hardware, such as Chia’s and Spacemesh’s proof-of-space, are in fact more wasteful than ASIC-able PoW, because they constantly burn the security budget.

Pro tip: When dating a Bitcoiner, never tell her you care about energy-efficient PoW. An immediate irreparable turn off.

Optimizing for the happy path

I would like to finish the blog by making a fool of myself and claiming that the most important threat model is when a no-attacker assumption is applied, formally, attacker_budget = $0 and attacker_rhashrate = 0%.

In many use cases the payee is not really concerned by the payer carrying out a double spend attack. E.g., in cup-of-coffee-type purchases, or when the merchant knows and trusts the payer—remittance, in-person payments, etc. In such instances, good UX implies a very fast first confirmation time, that is, a short time span between the user broadcasting the payment and the receiver observing it has been mined into the ledger.

This category includes also cases where the good or service paid for will only be delivered to the buyer at a later date. Such is the case in e-commerce which takes several days to ship, thus providing enough time for the seller before real harm can be done. And such is the case when trading crypto against a centralized exchange, or a crypto-to-fiat gateway, which settles the IOU at a later date, off-chain.

This time-to-first-confirmation metric is almost always overlooked, as researchers and devs tend to analyze the usability of respective blockchains in a principled methodology, and treat the first confirmation as merely one step towards sufficient (probabilistic) irreversibility of the state. However, while the system is only usable due to its robust worst-case guarantees, real-world usage frequently requires, simply, speedy inclusion in the ledger, which establishes the importance of the time-to-first-confirmation metric.

Importantly, note that in PHANTOM and many other DAG-based protocols, valid transactions that entered the DAG and that do not admit double spends will be accepted and admitted to the state regardless of the final ordering; in database language, they are commutative with respect to other transactions co-mined in the same level in the DAG. This implies that an attacker can reverse a payment only if he engaged directly with the victim, i.e., paid the merchant in exchange for another commodity or service and then went on to reverse the transaction. This is in contrast to a single-chain-based protocol where overriding the selected chain automatically overrides all transactions in it.7 When we refer to an attacker with attacker_rhashrate = 0 we do not assume, therefore, that 100% of the mining is done by honest nodes, rather that no attacker node engaged with the merchant directly in the to-be-confirmed transaction (or in very recent transactions on which this one depends).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a fast first confirmation is crucial for a good UX for the payer, regardless of the merchant’s waiting and authorization policy. Paying with crypto is an anxiety-inducing process, and an ordinary end-user wants to see the result of her attempts as fast as possible. Bitcoin’s ten minutes is just way too slow, it’s not the way money goes.

That’s the way the money goes

Impatience is a core trait of the Kaspa community. The main reason we are obsessed with DAGs is we want to see our transactions confirmed at Internet speed, similar to other web-based services. For use cases that require more than one confirmation we know to revisit the app later to check for the final status. Nevertheless, we need this speedy responsiveness out of the crypto app; we want a cryptocurrency to ping and be ponged, and we want it now.

Impatience will also motivate the smart contract layer design I will propose here [WIP], where I will suggest optimizing for speed rather than for decentralization. Stay tuned, and start getting used to instant confirmations.

Notes

-

Or maybe he just kept losing his private keys out of sheer cumbrousness, and he’s now very upset about this whole Bitcoin thing. ↩

-

One could challenge this claim if one could provide evidence that there aren’t enough financial instruments and liquidity to profit, in the mentioned order of magnitude, from an hours-long attack on Bitcoin; then one would need to provide a model for confirming transactions based on the existing financial liquidity for such manipulations. Until then, we’re good. ↩

-

This term has nothing to do with liquidity mining in DeFi. ↩

-

CapEx dominates in the initial days of the ASIC. Of course, as time develops the miner pays more and more OpEx. A mining-informed friend told me that a very rough approximation of the CapEx to OpEx ratio, at the end of the machine’s lifetime, is 1:1. A PoW system which goes more extreme on the CapEx side would use an optical PoW function, which uses cutting-edge optical computing chips. These chips run the central part of the computation on photons, whose interaction does not emit heat, in contrast to electrons running on wire. Also relevant is a paper by Ganesh et. al., suggesting virtual ASICs, a protocol that mimics any point on the CapEx-OpEx spectrum. ↩

-

(1) elapsed_time is the time that passed between the transaction being included in the block and now. (2) A more nuanced approach to the attack_cost paradigm would consider additionally the attack_success_probability, for the case of an attacker renting less than 50% of the hashrate. This does not change the qualitative differences between the paradigms, and so to keep things simple I assumed instead that the attacker is >50%, during the attack window, when attacking a liquid mining system. And vice versa: elapsed_time can be used in illiquid mining systems as well, to shorten confirmation times, if the client applies more sophisticated confirmation policies; see this paper. Still, accelerating block times would accelerate confirmation times in these policies as well. ↩

-

For instance, the bounds given by Satoshi on the attacker’s probability of successfully overriding the longest chain are calculated for an attacker that never abandons his one-shot attack, even if many blocks behind. Such an attacker is clearly not concerned with cost and profit. ↩

-

Admittedly, transactions removed due to chain reorgs can and in many systems are pushed back to the mempool. However, these transactions are not guaranteed to enter the blockchain in a relevant timeframe, either due to insufficient fees in the post-reorg congestion, or due to users keeping on transacting and innocently double spending previous payments. ↩